Accounting for PPP projects

Public-private partnership (PPP) projects can be complex to account for as they often combine aspects of construction, financing, operation and asset transfer. Depending on who controls the infrastructure and how the operator is compensated, different accounting standards may apply. In particular, IFRIC 12 (Service concession arrangements), IFRS 16 (leases), IFRS 15 (revenue from contracts with customers), and IAS 16 (property, plant and equipment) need to be considered when accounting for these projects. This article provides a high-level synopsis of the accounting treatment under each of these standards, with a focus on service concession arrangements under IFRIC 12. We also provide a summary table and simple illustrations of the financial asset and intangible asset models to clarify the key concepts.- Determining the right accounting model for a PPP

- Control of services and pricing:

The grantor - typically a public sector entity such as a government body, municipality or a government-owned agency - controls or regulates what services the private operator must provide with the infrastructure, to whom it must provide them, and at what price (or the pricing mechanism).

- Control of residual interest:

The grantor controls any significant residual interest in the infrastructure at the end of the term (e.g. ownership or beneficial right to take back the asset) (If the infrastructure is used up or has no residual value by end of the arrangement, this condition is considered met by default).

If both above conditions are met, the arrangement is a service concession within the scope of IFRIC 12. In such cases, the infrastructure is deemed controlled by the public sector and is not recorded as property, plant & equipment (PPE) on the operator’s balance sheet. Instead, the operator accounts for its rights and obligations under the concession by recognising either a financial asset or an intangible asset (or a combination of both), depending on the payment model. We discuss these models in detail below.

If the arrangement fails the IFRIC 12 control tests (for example, the private operator controls the use of the asset or retains the asset at the end), then IFRIC 12 does not apply. In that case, one must evaluate the PPP under other standards: it could be accounted for as a lease (IFRS 16) or as a normal contract with a customer (IFRS 15, with the asset possibly recognised under IAS 16 by the operator). In other words, arrangements where the grantor does not control the asset fall back on the usual IFRS framework for leases or sales/service contracts. An arrangement that meets the IFRIC 12 criteria cannot be treated as a lease by the operator, because the grantor’s control over the asset’s use and residual is incompatible with the operator having a lease‐type control of that asset. Indeed, IFRS 16 explicitly scopes out service concession arrangements that are within IFRIC 12.

- Accounting under IFRIC 12: service concession arrangements

- The operator does not capitalise the infrastructure as PPE on its books, since the asset is controlled by the grantor (public sector)

- The operator recognises revenue for construction or upgrade services as it performs those services, typically using IFRS 15 (percentage-of-completion or output method, if applicable) for performance obligations during construction. In practice, construction revenue is often recognised over time as the asset is built

- In exchange for construction services, the operator recognises either a financial asset or an intangible asset (or a mix of the two) as the ‘consideration’ it receives from the grantor. This classification depends on how the operator is compensated:

- If the operator has an unconditional contractual right to receive cash (or another financial asset) from the sponsor (e.g. fixed payments, etc.), it uses the financial asset model

- If, instead, the operator is given a right to charge fees to the public users of the infrastructure (and cash flows depend on usage/demand), it uses the intangible asset model

- Some concessions use a hybrid model where the operator receives some guaranteed payments and also has the right to charge users. In such cases, the operator splits the consideration into a financial asset component and an intangible asset component.

- During the construction phase, any consideration earned (whether it will ultimately be a financial or intangible asset) is typically recorded as a contract asset under IFRS 15, since the operator’s right to payment may be conditional on completing the construction performance obligations. Upon completion (or as milestones are reached), that contract asset converts into a receivable financial asset or an intangible asset, as appropriate

- The operator also recognises revenue over time for operating and maintenance services during the concession period (e.g. maintenance fees, operating payments), again following IFRS 15 principles for service revenue. The costs of operating the asset are expensed as incurred against this revenue

- On the balance sheet, under the financial asset model the operator will carry a financial receivable (loan or similar) due from the grantor; under the intangible asset model the operator will recognise an intangible asset (e.g. a licence to charge users) which it will amortise over the concession term. In both cases, profit is recognised on construction (if any), and subsequently the financial asset earns interest income or the intangible asset yields user-fee income, respectively.

Financial asset vs. intangible asset model – illustration

To visualise the difference between the two models under IFRIC 12, consider a simplified example of a toll road project:

- Financial asset model:

The government (grantor) agrees to pay the operator fixed annual amounts, regardless of how many cars use the road. The operator is essentially financing and building the road for the government, and the government will pay back the investment (perhaps with interest) over time. In substance, the operator has a financial asset (receivable) from the government.

- Intangible asset model:

The operator’s return comes directly from the public – for example, by collecting tolls from drivers for 20 years. The government grants the operator a licence to charge tolls, but does not guarantee any payments. Here, the operator’s right is an intangible asset (a licence to collect user fees).

Below are simple diagrams illustrating the cash flows and rights in each model:

-

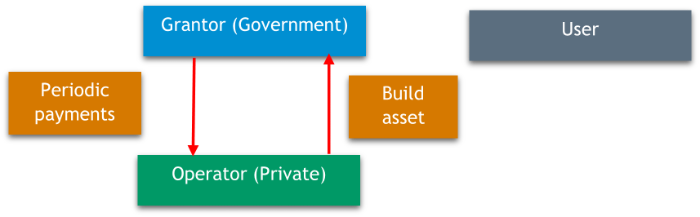

- Financial asset model:

The operator builds the infrastructure for the grantor and in return has an unconditional right to receive cash (e.g. periodic payments) from the grantor. The grantor effectively ‘pays for’ the asset over time, so the operator records a financial receivable and contract revenue for construction. The public may use the road, but the operator’s income is secured by the grantor (often reflecting a government guarantee) rather than directly from users:

-

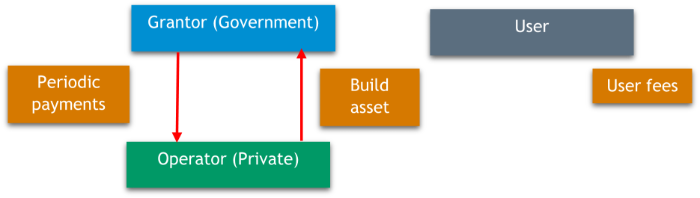

- Intangible asset model:

The operator builds the infrastructure and the grantor grants the operator a right to earn revenue from the public (e.g. collect tolls or fees). The operator’s cash flows depend on public usage. The operator records an intangible asset (the concession right) equal to the fair value of construction delivered, instead of a receivable. Over the concession, the operator earns revenue by providing access/service to users and amortises the intangible asset as it is ‘used up’ by earning those user fees:

Under both models, the initial construction revenue recognised is typically the fair value of the construction service provided. Interestingly, this means total revenue recognised differs between the models: in a pure financial asset model, total revenue equals the sum of payments from the grantor (e.g. equal to total cash inflows), whereas in an intangible model the operator’s reported revenue includes the construction revenue plus the subsequent user fees (since the intangible asset’s fair value is recognised upfront as revenue, and then user fees are also recognised as revenue when earned). However, the profit profile and cash flows are structured differently: the financial asset yields interest income and repayments, while the intangible asset model often results in higher reported revenue but with amortisation expense against it. In both cases, at the end of the term the infrastructure often transfers to the public authority (with no additional consideration), so the operator’s assets related to the project are fully settled (the receivable paid off or the intangible fully amortised).

-

- Hybrid models

Many real-world PPP projects have a mix of payment mechanisms – for example, the government might guarantee a minimum payment and the operator can also charge users a fee. IFRIC 12 allows bifurcating the arrangement into financial and intangible components in such cases. The operator would account for one portion of the project as a financial asset (for the guaranteed part) and another portion as an intangible asset (for the part dependent on usage). This requires a reasonable allocation of the construction revenue to each component, and then applying the respective accounting model to each. The hybrid approach ensures the accounting reflects the distribution of demand risk i.e. the part of the investment that is guaranteed by the grantor versus the part that is at the operator’s risk (recoverable only through public usage). The overall revenue and profit recognition follows the same principles of IFRS 15 during construction and operation phases.

- Other PPP arrangements (IFRS 16, IFRS 15, IAS 16)

-

- Lease arrangements (IFRS 16):

IFRS 16’s scope excludes IFRIC 12 arrangements, so this lease accounting is only appropriate if the arrangement does not satisfy IFRIC 12’s control tests. Another scenario is when a public authority provides an existing asset to the private operator via a lease (e.g. the city leases an existing bus terminal to an operator who will renovate and run it). If that asset use is conveyed by a lease contract, the operator (as lessee) would account for a right-of-use asset and a lease liability under IFRS 16 – unless the arrangement is structured such that IFRIC 12 still applies (IFRIC 12 can still apply in some cases where the grantor provides access to existing infrastructure, as long as the grantor retains control of it). The key is assessing who controls the use of the asset: IFRS 16 uses a similar control notion (right to control use of an identified asset), so an arrangement won’t be a lease if the public authority controls the asset’s use, since that would point to IFRIC 12.

-

- Construction or service contracts (IFRS 15 and IAS 16):

-

- Private sector asset (IAS 16) with service contract:

In this case, the private operator capitalises the infrastructure on its own balance sheet as PPE under IAS 16, and accounts for revenue from the public-sector contract under IFRS 15 (e.g. sale of goods or services, such as selling power or providing capacity). Essentially, the arrangement is treated as the company’s own asset used in its business, with the public entity simply a major customer, rather than a transfer of the asset or a concession. Normal depreciation and impairment rules apply to the asset, and the revenue is recognised according to the contract terms (which might be fixed payments or usage-based payments, akin to a commercial contract).

- Point of view:

In practice, however, governments usually structure contracts to clearly fall under one model or another. The table below summarises which accounting standard typically governs various types of PPP arrangements:

| PPP arrangement type | Characteristics | Summarised accounting treatment |

| Service concession arrangement (grantor controls use of asset) |

|

a. If paid by grantor → financial asset (receivable) model b. If paid by users → intangible asset (licence) model

|

| Lease (right-of-use) arrangement |

|

|

PPP arrangement type |

Characteristics | Summarised Accounting treatment |

| Construction contract (build-and-transfer) |

|

|

| Privately-owned asset & service supply (no public control of asset) |

|

|

How BDO can help

BDO’s expert financial accounting advisory services teams apply the practical experience and knowledge gained from working with clients locally and worldwide.

Please reach out to the relevant partner in your local BDO firm for further information.

Authors:

Abdul Sharjeel, Head of Advisory, BDO Saudi Arabia

Usman Siddiqi, Manager FAAS, BDO Saudi Arabia